Remembering nine former members of the National Spiritual Assembly

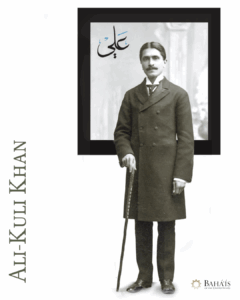

Ali-Kuli Khan was a distinguished diplomat, scholar, and lifelong servant of the Baha’i Faith. Born in 1879 in Kashan, Iran, to a noble family, Khan’s father was a mayor of Tehran who became a follower of the Bab. Khan, however, was raised by his mother and sisters as a Shi’a Muslim. Although he was taught that Baha’is were infidels, he embraced the Faith and as a youth traveled through Iran dressed as a dervish, boldly teaching the new religion.

Ali-Kuli Khan was a distinguished diplomat, scholar, and lifelong servant of the Baha’i Faith. Born in 1879 in Kashan, Iran, to a noble family, Khan’s father was a mayor of Tehran who became a follower of the Bab. Khan, however, was raised by his mother and sisters as a Shi’a Muslim. Although he was taught that Baha’is were infidels, he embraced the Faith and as a youth traveled through Iran dressed as a dervish, boldly teaching the new religion.

In 1899, driven by love for ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Khan left Tehran with no funds, and journeyed under difficult conditions to the Holy Land. There he served as an amanuensis to ‘Abdu’l-Baha, who in 1901, sent him to the United States to interpret for Baha’i philosopher, Mirza Abu’l-Fadl.

His impressive work as a diplomat was emblematic of his heartfelt wish to bring about ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s aim of, “establishing a perfect bond between Persia and America” (Promulgation of Universal Peace). In 1902, he became secretary to the Persian Minister in Washington, D.C., and in 1904, married Florence Breed, an American Bahá’í from Boston. Together they had three children. During the 1910s and 20s, Khan would go on to serve as Persia’s Chief Diplomatic Representative in Washington D.C., Istanbul, and throughout the Caucus region.

In 1912, Khan received ‘Abdu’l-Baha at the Persian Legation in Washington D.C. during the Master’s visit to America. Renowned for his powers of speech, Khan once delayed the sailing of an ocean liner because an important Persian dignitary was held up at one of his talks. Drawing from his deep philosophical understanding gleaned from ‘Abdu’l-Baha and Mirza Abu’l-Fadl, Khan taught many souls who embraced the Faith.

Throughout his life, Khan served on Baha’i bodies including Local Spiritual Assemblies in New York, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles, as well as the Baha’i Temple Unity, an organization formed to coordinate the planning and construction of the first Baha’i House of Worship in North America. Khan was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States and Canada in 1925.

Khan passed away at 79 in Washington D.C., where he spent much of his life. A portrait of a young Khan by Alice Pike Barney now hangs at the Smithsonian Museum.

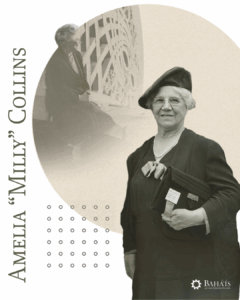

Amelia “Milly” Collins was born in 1873 in Pittsburgh and was one of fourteen children. From an early age, she showed a fascination with ornate gates, which she would create for her dollhouses, and dreamt of having one of her own. This childhood dream would come full circle when Shoghi Effendi named the main gate to the Shrine of Baha’u’llah in her honor.

Amelia “Milly” Collins was born in 1873 in Pittsburgh and was one of fourteen children. From an early age, she showed a fascination with ornate gates, which she would create for her dollhouses, and dreamt of having one of her own. This childhood dream would come full circle when Shoghi Effendi named the main gate to the Shrine of Baha’u’llah in her honor.

As a young woman, Milly married Thomas Collins, a successful mining engineer. The couple’s financial prosperity allowed her to devote time and resources to service after she became a Baha’i in 1919. In a letter that year, ‘Abdu’l-Baha expressed His hope that she would become “a heavenly soul” and “erect a structure that shall eternally remain firm and unshakable.”

During the following decades, Collins served for more than twenty years on the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada and held roles on committees including the National Teaching, Assembly Development, and Inter-America Committees. During the first and second Seven Year Plans (1937-1953), she traveled extensively, assisting with the consolidation and teaching efforts of Baha’i communities across North, Central, and South America.

In 1937, Shoghi Effendi entrusted Collins with a sacred gift for the American Bahá’ís: a lock of Baha’u’llah’s hair. Collins presented it in 1938 at the National Convention, a yearly gathering where Baha’i delegates consult and elect the National Spiritual Assembly, where it became the first of many sacred items housed in the National Baha’i Archives.

Collins was a loyal companion of Shoghi Effendi, committed to fulfilling Abdu’l-Baha’s wishes in His Will and Testament that the friends should make the Guardian happy. After arranging her estate, she provided the means for establishing vital institutions at the Baha’i World Center, including covering much of the cost for the superstructure for the Shrine of the Bab.

In December 1951, Shoghi Effendi formally appointed Collins as a Hand of the Cause of God, a title given by Central figures of the Faith, to individuals recognized for their extraordinary efforts in promoting and protecting the Faith, and Vice President of the International Baha’i Council.

Even in her final years, she was wholeheartedly committed to serving the Faith, participating in gatherings despite physical ailments. On January 1, 1962, Collins died in Haifa at 91, in the embrace of Ruhíyyih Khánum. Her life remains an inspiration of steadfast love, service, and sacrifice.

Helen Elsie Austin was an attorney, diplomat, and devoted servant of the Baha’i Faith. Born in Alabama in 1908, she moved with her family to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1920. Her parents, both educators, worked at the Tuskegee Institute and encouraged their children to pursue education and work towards the advancement of their people.

Helen Elsie Austin was an attorney, diplomat, and devoted servant of the Baha’i Faith. Born in Alabama in 1908, she moved with her family to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1920. Her parents, both educators, worked at the Tuskegee Institute and encouraged their children to pursue education and work towards the advancement of their people.

Throughout her experiences in education, Austin experienced racial discrimination and was one of only seven Black students at her university. Notwithstanding, she became the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Cincinnati’s College of Law. In 1930, she passed the Indiana bar exam, joining a pioneering group of Black women lawyers in the United States.

Austin was introduced to the Baha’i Faith in the early 1930s and after two years studying its teachings, she enrolled. It was her interactions, especially with Louis Gregory and Dorothy Baker, that helped her spiritually resolve her growing pessimism toward racism in American society. “The religion of Baha’u’llah, begins with that essential spiritual regeneration of the human being, which creates a heart for brotherhood and impels action for the unity of mankind,” she later said.

That year, Austin represented the NAACP in its protest of allocations of public school funding, as segregated Black schools were underfunded in comparison to ones for white students. After receiving her honorary doctorate at Wilberforce University, in 1937 she became the first Black woman to serve as Assistant Attorney General in Ohio.

Austin’s Baha’i service was expansive. She was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada in 1944 and, after a pilgrimage to Haifa, pioneered to Morocco in 1953, earning the title “Knight of Baha’u’llah, given to the first Baha’is to settle in new areas to share the Faith.” She helped form Baha’i communities across Africa while working as a U.S. cultural attaché in Nigeria and Kenya. In 1963, while serving on the National Spiritual Assembly of North West Africa, she participated in the historic election of the first Universal House of Justice.

The service rendered to humanity by Dr. Austin left a legacy of distinction that will echo and inspire generations to come. At 96, she passed away on October 26, 2004 in San Antonio, Texas.

Born in Dabney, North Carolina, on September 11, 1881, Matthew Washington Bullock’s life was characterized by a deep commitment to justice. His parents were enslaved before the Civil War, and his grandfather was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. The Bullock family eventually relocated to Massachusetts to escape racial persecution.

Born in Dabney, North Carolina, on September 11, 1881, Matthew Washington Bullock’s life was characterized by a deep commitment to justice. His parents were enslaved before the Civil War, and his grandfather was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. The Bullock family eventually relocated to Massachusetts to escape racial persecution.

In 1900, Bullock enrolled at Dartmouth College where he joined the glee club and chapel choir, served as editor of The Aegis, and played football. During an away game at Princeton University, Bullock was the victim of a violent racist attack by a Princeton player.

Bullock went on to graduate from Harvard Law School where he supported himself by coaching football. In 1910, he married Katherine H. Wright and they had two children, Matthew Jr. and Julia.

His career spanned the fields of education and law. Among his countless accomplishments, Bullock served as a dean at Alabama A&M, and on the Massachusetts Parole Board from 1927 to 1937, where he focused on prison reform and advocating for just policies.

Bullock learned of the Baha’i Faith from Ludmilla Bechtold Van Sombeek, whom he referred to as his “spiritual mother.” Bullock declared his belief in Baha’u’llah in 1940. With this renewed understanding, Bullock’s life of service only intensified.

In 1947, Bullock became a member of the Boston Local Spiritual Assembly. That same year he co-authored “A Baha’i Declaration of Human Obligations and Rights for the United Nations.” In 1952, Bullock was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States and visited the Holy Land where he met with Shoghi Effendi. He described this experience: “I don’t think I will ever be able to express what it meant to me; nor do I think that any Baha’i is the same after being with the Guardian. I wish every Baha’i could have the bounty which has been mine.”

In 1953, Bullock transitioned from his service on the NSA to respond to the needs of the Ten-Year Crusade, a plan to spread and strengthen the Baha’i Faith worldwide. He pioneered in Curaçao and was named a Knight of Baha’u’llah, later teaching the Faith across the Caribbean, Africa, and Latin America. Bullock spent his final years in Detroit near his daughter, and passed away on December 17, 1972, after a long life of immense bravery and resilience.

A humble servant and life-long lover of music, Charles Wolcott was born in Flint, Michigan, in 1906. His father was an accountant whose true passion was for music and passed that love to his son. Wolcott grew up playing piano and accordion in small town orchestras. By high school, he led a student dance band, a talent he carried to the University of Michigan and eventually into the vibrant music scene of 1920s Detroit.

A humble servant and life-long lover of music, Charles Wolcott was born in Flint, Michigan, in 1906. His father was an accountant whose true passion was for music and passed that love to his son. Wolcott grew up playing piano and accordion in small town orchestras. By high school, he led a student dance band, a talent he carried to the University of Michigan and eventually into the vibrant music scene of 1920s Detroit.

After marrying Harriett Marshall in 1928, the couple moved first to Toronto and then New York City—a bold move during the Great Depression, yet Wolcott thrived. As a pianist, composer and arranger, he worked with big band musicians and wrote scores for Columbia Records. It was in New York City in 1935 that he and his wife were first introduced to the Baha’i Faith, formally embracing it in California two years later.

In 1937, Wolcott began his career at Walt Disney Studios, composing for the classic animated films Bambi and Pinocchio, and later serving as the studio’s General Music Director.

Wolcott’s decades of service to the Baha’i Faith were the deepest chord of his life. Wolcott was active on Baha’i committees including his role as Chairman of the Inter-America Committee, responsible for coordinating teaching efforts in Central and South America, and Vice-Chairman for the National Audio-Visual Education Committee. He was then elected to the Los Angeles Local Spiritual Assembly in 1948, and in 1950 served for two years on the American Southwest Teaching Committee.

Wolcott was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly in 1953. Following the passing of the Guardian in 1957, the Baha’i world was thrust into a new era. In 1960, when Hand of the Cause Horace Holley left his position as NSA Secretary to serve as one of the World Center’s custodians, Wolcott was elected as the new Secretary and relocated with his wife to Wilmette, Illinois.

The couple moved to Haifa in 1961, when he was called to serve on the International Baha’i Council, before being elected to the first Universal House of Justice in 1963. Thus began a 26-year period of service to that sacred institution. He died on January 26, 1987 in the Holy Land. The Wolcott’s two daughters, Marcia and Sheila, both served the Faith with great distinction, continuing the family’s deep spiritual legacy.

Hugh Chance was born on December 28, 1911, in Winfield, Kansas. He spent his early years on a farm, riding two miles on horseback to school and helping with farm chores. After high school, he attended Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, where he met and later married Margaret Chamberlain.

Hugh Chance was born on December 28, 1911, in Winfield, Kansas. He spent his early years on a farm, riding two miles on horseback to school and helping with farm chores. After high school, he attended Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, where he met and later married Margaret Chamberlain.

After college, Margaret worked as a schoolteacher while Hugh worked as a janitor and held other jobs to pay his way through law school, earning his Juris Doctor in 1934. They had two children—Mary Ann in 1937 and Robert in 1942, who died the following year.

In 1943, Chance enlisted in the U.S. Navy. Before departing, his father told him, “If you’re ever in Australia, look up the Boltons.” While stationed there, Chance visited the Bolton family and noticed a quote on their wall. They explained it was from the Baha’i Faith and gave him some pamphlets. Though not initially interested, he sent them home to his wife and daughter.

After his military term, Chance became legal counsel for the International Chiropractor’s Association. In 1953, the Boltons visited the U.S. for the dedication of the Baha’i House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois, and stayed with the Chance family. Their visit led Margaret and Mary Ann to further explore the Baha’i Faith; both became members that year.

In 1954, Chance reluctantly attended a Baha’i conference and, moved by what he heard, accepted the Faith. He was soon elected as a delegate to the National Convention and appointed to the National Teaching Committee.

In 1961, following Charles Wolcott’s departure to Haifa to serve on the International Baha’i Council, Chance was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly as its secretary. When Wolcott told him, “You’ll be in Haifa some day,” Chance was skeptical.

Two years later, at the First International Convention in Haifa, Chance was astonished to hear his name called as one of the nine members elected to the first Universal House of Justice. Initially hesitant to serve due to family obligations, circumstances miraculously shifted, allowing him to accept. As a lawyer, he was instrumental in drafting the Constitution of the Universal House of Justice, completed in 1972. He served on the House of Justice for 30 years.

In 1993, the Chances retired to Winfield, Kansas, joining its local Baha’i community. Margaret died in 1996, and Hugh, despite declining health, participated in the Kansas Baha’i centennial in 1997. He died in 1998. The two are buried in Tisdale Cemetery near Winfield.

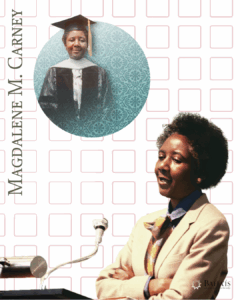

Born in rural Tennessee in 1929, Magdalene M. Carney—educator, civil rights advocate, and devoted Baha’i—was the eldest of eight children. She helped raise her siblings while working the family farm, and later wrote that from a young age, bore the responsibility of modeling moral integrity for her siblings.

Born in rural Tennessee in 1929, Magdalene M. Carney—educator, civil rights advocate, and devoted Baha’i—was the eldest of eight children. She helped raise her siblings while working the family farm, and later wrote that from a young age, bore the responsibility of modeling moral integrity for her siblings.

Carney was determined to obtain an education that was denied to her forebears—her grandfather having been released from slavery when he was 17, her mother having a third grade education, and her father giving up his formal education to work on the farm. She made a private vow: to educate herself and uplift her family from poverty. Her resolve was evident early on. Once, at age nine, she was hoisted onto a plow horse during a blizzard, burlap-wrapped feet braving the frost, determined to reach school. She was the only student to make it to school that day.

Carney went on to earn degrees from Tennessee State, George Peabody College, and ultimately a doctorate in education from the University of Massachusetts. Her work spanned classrooms and civil rights efforts, including leading a successful nonviolent desegregation initiative in Mississippi in 1969.

Carney embraced the Baha’i Faith in 1962 after reading a simple pamphlet given to her by a professor. “Unimaginable joy flooded my heart,” she later recalled. From that moment, she became a tireless teacher of the Faith, eventually serving on the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States from 1970 until 1983, and later in Haifa, Israel, as a Counselor member of the International Teaching Center.

Her life touched continents—educating, inspiring, and building community. She passed away in 1991 and is buried on Mount Carmel in Haifa. The Magdalene Carney Baha’i Institute continues her legacy, fostering education in the southern United States, particularly among children and youth—just as she had always dreamed.

Eleanor Moon (Soo) Fouts, a faithful maidservant of the Cause and an astute businesswomen, was born in Maui, Hawaii, in 1923. Of Korean descent, she and her five siblings were raised on a plantation where her father worked as a night watchman. Despite limited means, her parents provided a joyful upbringing and found a way to enroll her and sister at an English-speaking school nearby.

Eleanor Moon (Soo) Fouts, a faithful maidservant of the Cause and an astute businesswomen, was born in Maui, Hawaii, in 1923. Of Korean descent, she and her five siblings were raised on a plantation where her father worked as a night watchman. Despite limited means, her parents provided a joyful upbringing and found a way to enroll her and sister at an English-speaking school nearby.

At six or seven years old, Fouts began attending a local Baha’i children’s class where her love for Baha’u’llah took root. “I was entranced by Baha’u’llah’s beauty and station and just accepted Him. Baha’u’llah simply became a part of me.”

While working as a clerical typist in Honolulu, she met her husband, Leroy Fouts, a serviceman engineer. They were married and had their first child. In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Fouts experienced racial prejudice, but her devotion to teaching the Baha’i Faith — which transcended race, color, or creed — sustained her.

Her husband’s career and Fouts’s dedication to travel teaching led her to many places including Utah, Michigan, New Jersey, Virginia and Florida. She served at local, national and international levels for more than 54 years. Fouts served as a U.S. representative to the United Nations Conference to Combat Racism and Racial Discrimination in Geneva in 1978, and for five years on the Baha’i National Teaching Committee of the United States.

In 1976, she became the first Asian woman elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’iss of the United States where she served until 1986. Fouts was also often asked to serve as an international emissary for the Assembly and traveled to Australia, Switzerland, Germany and Samoa.

After the death of her beloved husband, Fouts pioneered in her mother country of Korea. She lived in Seoul for nine years before returning to the United States at 80.

Fouts died on February 9, 2016 in Deerfield, Illinois. She was 92.

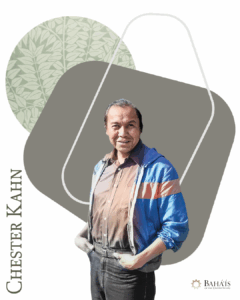

A gifted visual artist, educator and devoted member of the Baha’i Faith, Chester Kahn, also known as Tso Yazzy (Little Water), lived a life deeply rooted in both his spiritual convictions and Navajo heritage. Kahn was raised in Pine Springs, Arizona, on a Navajo reservation where his community lived off the land and in coherence with their spiritual beliefs.

A gifted visual artist, educator and devoted member of the Baha’i Faith, Chester Kahn, also known as Tso Yazzy (Little Water), lived a life deeply rooted in both his spiritual convictions and Navajo heritage. Kahn was raised in Pine Springs, Arizona, on a Navajo reservation where his community lived off the land and in coherence with their spiritual beliefs.

At age 12, Kahn was sent to the Bureau of Indian Affairs mandated boarding school, where Native American children were separated from their families, coerced into foregoing their religious traditions, and indoctrinated with Christian beliefs. While living in Reno, Nevada, Kahn befriended two white Baha’is and was surprised to discover that embracing this new Faith didn’t require him to distance himself from his culture, but rather, it deepened his understanding and connection to Navajo spirituality and traditions. In 1962, at 26, Kahn became a Baha’i.

Throughout his life, Kahn traveled extensively across North America, sharing the message of Baha’u’llah among Native American communities including the Sioux, Omaha, Iroquois, and the Indigenous peoples of Alaska, Canada, Oklahoma and Wyoming.

In 1965, Kahn was appointed by the Board of Counselors as an Auxiliary Board member for Propagation while living in the Arizona region. He served in this capacity until 1972 when he retired due to the growing demands of his service-oriented career.

Khan moved his family, including six children, to direct the Chinle Agency office of the Office of Navajo Economic Opportunity (ONEO), appointed by Navajo Tribal Chairman, in 1968. In addition to his professional life, Khan was renowned in the Native American community for his visual artistry. His most famous work is the collection of murals, “Circle of Light” which took him seven years to complete and is composed of 65 portraits that depict Navajo people.

He served as a delegate to the National Baha’i Convention and was elected as a member of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States from 1982-1989. His brother Franklin Kahn was the first Native American elected to the NSA, and finished his service with the institution just a year before Chester was elected. Chester’s story stands as a testament to the spiritual transformation that unfolds when one opens their heart to Baha’u’llah—a choice that shaped and uplifted generations of his family through their devoted service to the Cause.

Kahn passed away at 83 on June 1st, 2019, in Apache County, Arizona.