When a charter school in Fresno, California, closed in 2014, it forced a transition for a Baha’i-initiated junior youth group that had thrived there.

Fortunately, with most students from the closed school ending up together at a middle school, the group’s facilitators found an opening to introduce the junior youth program to middle-school personnel.

And the relationships still growing around it — among the Baha’i community, the facilitators (known as animators), school administrators and teachers — are helping make the program special for students and sustainable.

That process is made easier as school officials see the junior youth program helping kids “with their power of expression, with their sense of ownership over the progress of their community,” says Sana Rezai, a Baha’i who moved to Fresno in 2014 to help build community in neighborhoods there.

“The trust extended by administration is a sign of the impact the program has made on the school,” Rezai observes: “that a religious organization is allowed to make lunchtime and classroom presentations.”

A connection and partnership

The initial pitch to the middle school’s administrators as the new term began in fall 2014 was simple, says Rezai: “Your students have really benefited from the program, which aspires to help middle-schoolers not only transcend the challenges of early adolescence but also contribute to building a new society. Could we use classrooms after school for meeting space?”

Says Rezai, “These two factors helped administrators feel connected to the program and feel like they are making a contribution from the outset.”

Too, he says, they felt “a sense of confidence in that this is an established and organized program with which they can have a partnership.”

No surprise the junior youth program took off at the middle school. That meant the animators could turn attention that fall also to the elementary school across the street, knowing that the sixth-graders there would soon be making the transition to middle school.

The approach to administrators at the elementary school? You guessed it: “The junior youth program is making a difference in the lives of middle-school students. May we use classroom space so sixth-graders can take part in this valuable program?”

“The principal loved the idea,” says Rezai, “knowing that these sixth-graders would then enter middle school and their animator would follow them and there would be something consistent during their transition.”

A cyclical system takes shape

But soon there would be another transition: middle-schoolers who have been through the program would be moving into high school. Their spiritual development could be enriched if they could undergo training to initiate, sustain and expand the junior youth program or other community-building activities.

So, Rezai recalls, the animators approached the local high school and described the groups that have been active in the middle and elementary schools that feed students to it.

“We then presented the idea that these high-schoolers can go back and be mentors to junior youth at their own middle school,” he says.

“The fact that we had personal relationships with the middle school and elementary school principals lent us a degree of trust with the high school administration, which was larger and less personally approachable.”

Thus the high school’s officials let the animators into classrooms to make presentations on the potential of youth, the role of an animator, and the training institute process that supports it all.

That, to Rezai, solidified a cyclical system “of students moving from elementary to middle to high school, each with an educational program for their age group, the high school program being one that trains them to go back to elementary and middle school as animators.”

A high level of trust and understanding

The growing relationships in the past five years, especially between animators — many of them youths — and administrators, have helped make it all possible.

“Our relationship with the middle-school principal in particular has continued to strengthen. One of the animators happened to get a job as a teacher at that middle school, further deepening ties between the junior youth program and the school,” notes Rezai.

More recently, the high school principal has begun asking teachers which students they think would be a good fit to be trained as animators, “and our outreach is more targeted to them in addition to just general lunchtime outreach.”

The principal also “advises us which classrooms to make presentations to and which clubs to reach out to,” says Rezai. “He even helps us speak with coaches and teachers when students want to be in the junior youth group but also are in sports or have after-school commitments.

“Because of this, the junior youth groups that have started more recently are higher quality and more sustainable.”

Rezai attributes that to a high level of trust and a mutual understanding about the aims of the junior youth program that has emerged among the local Baha’i community, animators, administrators and teachers.

While inspired by principles of the Baha’i Faith, the junior youth program is designed for participants and animators of all faiths as it “aims to empower junior youths both spiritually and materially.”

So even when the program’s most visible spokespeople are animators or school officials who otherwise have little or no knowledge of the Baha’i Faith, the Baha’i community is comfortable helping set the program in motion and lending support when needed.

A language that’s simple and profound

The junior youth program’s success, Rezai says, relies greatly on how it’s explained.

For example, the initial pitches to youths and administrators “use language that is simple and profound, that conveys the essentials in an accessible way,” he says.

This habit of speaking “in full and complex thoughts yet in a simple and inclusive way” then enables administrators and youth animators to also do the same. “It’s amazing to hear them speak about the program in their own words with such simplicity yet with depth.”

To Rezai it’s “about creating a culture in which everyone is both contributing what they are learning and also benefiting from the experience of others. So with all this, the capacity of the youths and the administrators will increase over time.”

A sense of giving back for animators

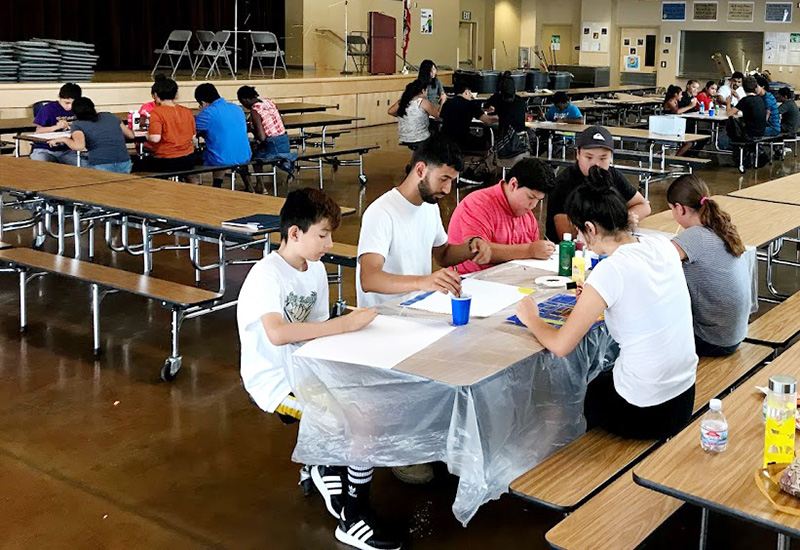

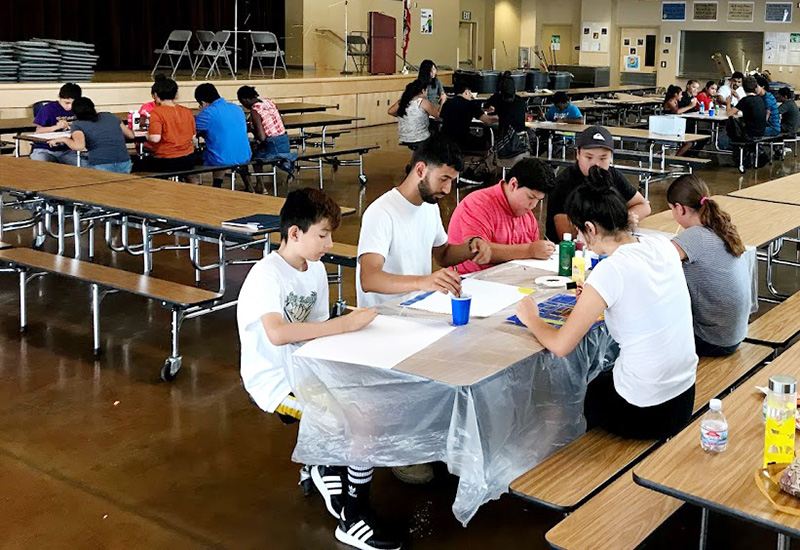

How do Fresno’s young animators see their role in fostering the growth of the junior youth program?

Kailen Castillo was a senior when she and other animators began reaching out to the high school in 2014. She and other animators strive to connect with people who “have the same vision to make sure we provide the best education for students but also make sure they’re involved in positive things,” she says.

Getting to know the high school’s activities director and the middle school’s leadership teachers “really helped in being able to reserve a space at school and helped us become more welcome,” she says.

A further benefit to the program was having junior youth groups meet in the schools, says Castillo. “I think it opens the door to the friends of those who are participating because they see they’re in a group at school and they can’t help but ask, ‘What are you doing?’”

Sahida Lara has the unique perspective of having participated in a junior youth group and then, on turning 15, training to become an animator. She has seen her old middle school open its arms to an opportunity for junior youths “to express themselves, expand their mentality, think outside the box and be more aware of their surroundings.”

Lara, who graduated from high school in June, says dropping in to see the principal has been “cool. Sometimes he asked me how the junior youth group is going, what’s everyone up to, what is your progress. I would say everyone is doing well, we’re expanding our minds more and more and expressing ourselves, and more people are getting involved.”

Adds Marina Lua, who also is animating where she attended middle school, “Now I’m able to give back to my middle school. The teachers were encouraging me to come back and give back.”

Talking frequently with administrators and teachers, she says, “helps us understand the reality of the kids that we’re going to be working with.”

As junior youths make the transition to high school, however, it’s difficult for them to remain active with the process, says Lara.

“In middle school we had a tiny world and we would meet right after school. But in high school, after school you end up having stuff to do, so that was a little hard. In high school you’re in a bigger world, faced with a bigger reality.”

Still, nearly 50 high school students have completed Book 1, Reflections on the Life of the Spirit, in a curriculum designed to train individuals for service to their community, says Rezai.

A blessing and a challenge

Sagar Das’s blessing — and challenge — was that for the past two years he taught at the middle school where his junior youth group meets.

He learned about the job opening there because he was an animator. That’s a plus in that he knew the school and its leadership already, but he also had to learn how to separate the two roles.

“Sometimes I would see my ‘teacher self’ while animating and sometimes I would see my ‘inner animator’ when teaching,” says Das, who is teaching at a different school this fall.

“There are interchangeable skills here, but they need to be used in a tactful way. As an animator it is easy to talk to the principal because he had known me for three years now, but as a teacher he wanted me to gain skills that an animator doesn’t normally need to use.”

The difference between a junior youth group and the classroom, the principal told him, is that in a classroom students are forced to be there.

“Some days, going straight into my junior youth group after a long day of work was difficult — especially since it’s the same setting. Most of the junior youth saw me as a teacher, so I was caught doing a lot of classroom-type corrections during group,” says Das.

Another challenge, he says, centers on visiting the homes of participants’ families, an integral part of the junior youth program. “There is a fine line of appropriateness for a school official to visit a student at their home. So home visits can become an issue, while an animator who is not a school employee can visit a home without any problems.”

Overall, though, “Being on the school site makes it so easy to have a junior youth group and have the principal, administration and parents on your side. I was seen on campus as someone committed to the neighborhood and its well-being.”

A building of capacities to serve

Hearing those comments, Rezai reflects that “over time, the benefits or challenges of various settings — whether school, neighborhood, etc. — are all just capacities that animators will gain, and they’ll be able to implement the program in many settings.” That includes places where junior youth groups are formed through neighborhood outreach rather than being connected with public schools.

For example, he says, “Many animators like [conducting the group in] a school because of the structure it provides.” Conversely, “Many animators like neighborhood settings because of the relationship with parents,” which helps them in engaging families in the process.

In any case, he says, “The capacity is difficult to learn and the setting compensates. But over time our capacity grows.”

For those who have brought the junior youth program to life in Fresno schools, building their capacity to work together has made all the difference. After all, it’s for the benefit of the students they serve.

![]()

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.